Lately it has become en vogue to create documentaries from the (visual) archives of the 20th century. This genre is often undertaken with a degree of artistic liberty that undermines the historical documentary value, and African Mirror – which had its world premiere in this year’s Berlinale – is a prime example of this.

Archival footage, letters, news clippings and diaries are sampled into what the director Mischa Hedinger calls a film essay that portrays the gaze, mindset and popular impact of the Swiss travel writer, photographer, filmmaker and public speaker René Gardi (1909–2000).

Unnamed, unspecified and voiceless

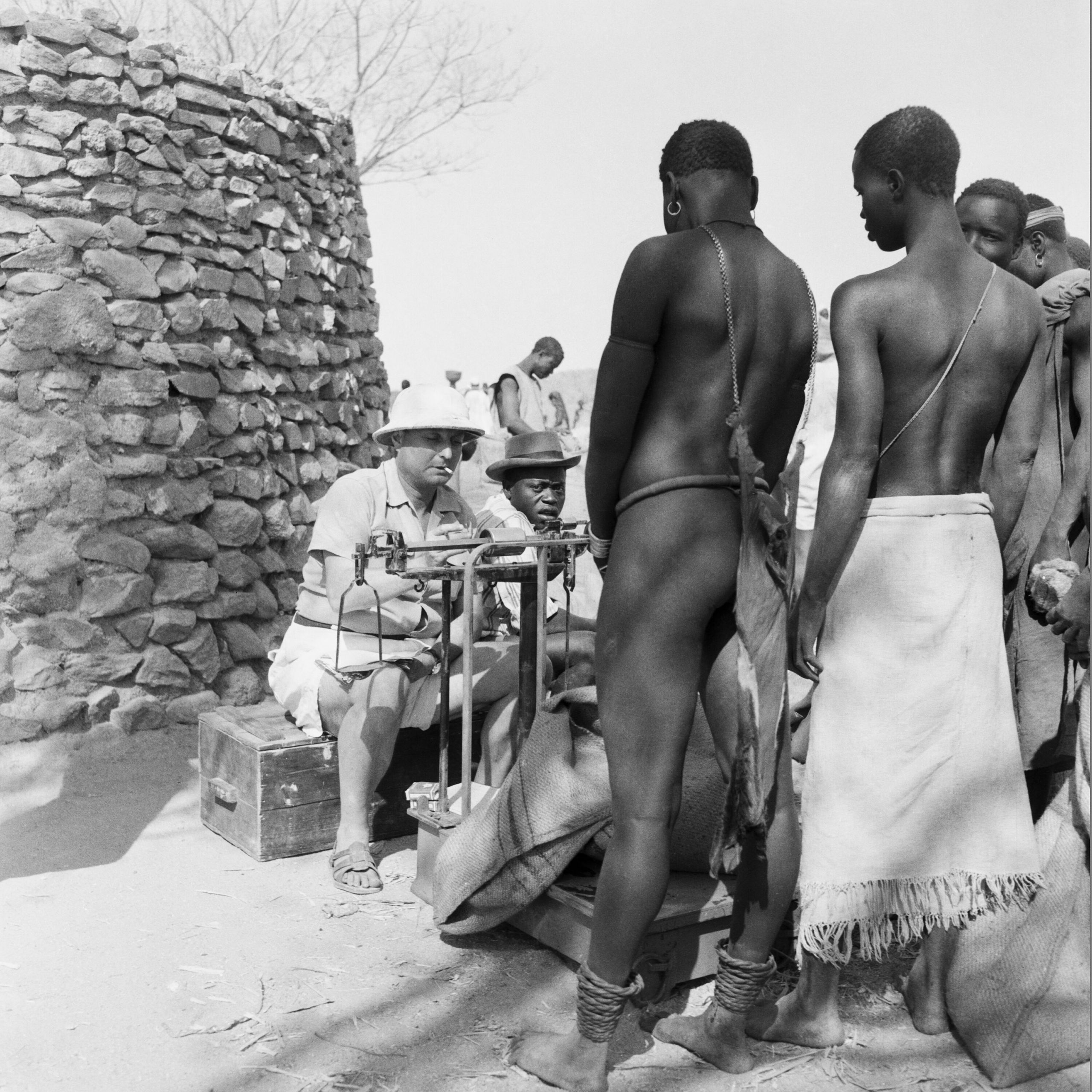

Throughout his career, Gardi travelled extensively in the African continent, particularly the part that is now the Republic of Cameroon. As in other documentaries in this genre, however, the viewer only far into the documentary realises where in the African continent the footage is from, and very few details are provided about the actual locations. The native people on display in Gardi’s footage – who appear without comment or credit in the film essay – remain unnamed, unspecified, and voiceless, whereas the colonisers populating the footage, and thus the film essay, are named, their merits specified, and their opinions and world views are given voice.

We see the colonisers perform and talk about their practices of census and tax collection for which insubordination is punished by burning down the houses and farmlands of the native population.

Native populations are not only denied their own voice but assumed to be voiceless in their constructed primitivism.

In other words, those who speak and those who observe in African Mirror are, once again, the white Europeans, thus reproducing the colonial gaze and the power of representation. This composition dismantles any kind of critique of colonialism that may or may not have been part of the director’s agenda. It is hard to see what kind of legitimacy such a distribution of the colonial gaze ever had, and, even more so, what kind of legitimacy a re-distribution and – in essence – rehabilitation, has today.

Manipulated documentation

In African Mirror the spectator is taken along on the travels of René Gardi, who laments that his native country Switzerland does not have its own colonies and thus does not contribute to the – in his view – at once noble and destructive task of civilising black populations in foreign territories.

The interesting feature of the film essay is the time journey that shows how the popular European reception of Gardi’s work changed from celebration and high demand to scrutiny and critique for its colonial and increasingly out-dated gaze. The footage and voiceovers of Gardi resemble animal recordings: native populations are blatantly exposed in their most intimate moments and without consent, commented on by the person behind the camera and not only denied their own voice but assumed to be voiceless in their constructed primitivism.

One of Gardi’s techniques was to persuade – sometimes with some form of meagre payment – the native people he came across to perform what he imagined were their «authentic» traditions in front of the camera. If they refused or objected to his ideas of what their traditions were, he would respond by insisting on them following his lead.

It does have some value to expose such practices of people who were once perceived as truth witnesses of the exoticness of the «other», but in the form this exposure takes in African Mirror the ridicule is inflicted once again upon the objects of colonial voyeurism.

Those who speak and those who observe in African Mirror are, once again, the white Europeans.

By devoting extensive time to displaying Gardi’s work uncommented, Mischa Hedinger commits the classic crime of re-assaulting the people on display. Whatever the point, there really is no excuse for this. If the point is to examine the colonial gaze, the archive of Gardi should be moved to Cameroon and made available to filmmakers and researchers there. If the footage belongs to anyone, it is to the descendants of the people so disrespectfully turned into the nostalgic hobby and career of a self-impressed Swiss camera owner.

Colonial imagination reimagined

Late in the film essay Gardi’s voice (probably reconstructed from letters and diaries) wonders, tormented, what happened to «his» authentic freedom paradise in the place that had since become independent Cameroon, catering to European tourism and post-colonial exploitation mixed with attempts of self-assertion, self-respect and self-reliance – attempts that were widely viewed as ridiculous and pathetic by both Gardi and the former colonial administrators. This lost place and time that Gardi longs for is a place where he had the freedom to subject the inhabitants to his desires and imaginations, and impress his European audiences with his assumed insights, interpretations and representations.

While the legacy of Gardi and the likes, of colonial administrators and delighted white European audiences lingers on, African Mirror contributes – whether willingly or not – to sustain these unequal powers of representation, and as such is a mirror of nothing but itself.