Let me write about an important niche of documentaries. This spring, observational documentaries were focused on at the 25th Thessaloniki Documentary Film Festival.

In a film world dominated by one-character-driven three-act narratives, there is a growing need for documentaries that depart from this formula. With the festival’s concept, «The Art of Reality Beyond Observation», and many observational films screened – both written texts and film examples marked this great alternative.

So, what does it mean to work ‘observational’? Maybe audiences are getting back some of the wonders of witnessing the spontaneity of life felt in the early days of cinema? Or if that is hard to do today, maybe the observational style gives more to the audience as a mode of human inquiry?

This is more show than tell. Independent scenes are shown after another – like the ones of Nikolaus Geyrhalter in Homo Sapiens (2016), with a mass of 15–30 seconds shots, without any classic drama, narration, voice-over, or humans shown at all. But the landscapes, buildings, and structures shown in the film are fascinating. As Geyrhalter uses long shot durations and a fixed camera in such a film, the details in the frames are also slowly disclosing themselves as we watch.

No narration

Observational cinema was influenced by three predecessors: Italian neorealism, French cinéma vérité, and American direct cinema. The first was highly critical, emphasising the economic and social realities of the time after 2nd WW. Cinéma vérité observed contemporary society up close, capturing life with handheld cameras etc., to convey authenticity and realism. They both were presenting lived experiences rather than providing ‘information’. The third influence, direct cinema, starting with people like Robert Drew and Richard Leacock, aimed to record life «as it is». Like Drew once wrote against narration, they would «invite viewers to think for themselves, without intermediary, narrator, or correspondent. They invited them to be puzzled, confused, surprised …». He ended his text in Imaging Reality (1998) with «Narration is what you do when you fail.» And as Leacock once told Orwa Nyrabia and me in an interview we did in Helsinki in 2008: «I don’t like the word ‘director’. I like the French word better, ‘réalisateur’. You realise the film, you don’t direct it. You don’t tell the film how to be.». And a year before Albert Maysles died, he told me, «Too many documentary filmmakers are still depending on narration to tell what’s going on.»

Observational and participatory cinema bear witness to events. The filmmaker spends a long time with their subjects, creating a mutual familiarity. You can recognise such in filmmakers as Nick Broomfield, Kim Longinotto, Nicolas Philibert, Sergei Dvortsevoy or Michael Glawogger.

In a film world dominated by one-character-driven three-act narratives, there is a growing need for documentaries that depart from this formula.

A filter instead of director

Twenty-five years ago, the first Thessaloniki documentary festival opened up for video, launching a «digital democratisation». The long-time festival director Dimitri Eipides selected through his years, especially 150 observational films – according to Apostolos Karakakis, in one of the festival’s texts. Several of these were long-term observations of local spaces, such as schools, hospitals, parks, prisons, or a recent election campaign (remember here Primary, 1960). These many ‘microcomosis’ made up a kind of Greek vérité.

This year in Thessaloniki, a large program was curated, featuring some of the greatest international observational documentaries, ranging from Nanook of the North (Flaherty); Shoah (Lanzmann); Salesman (Maysles); Divorce Iranian Style (Longinotto); up to the more recent Austerlitz (Loznitsa); The Dazzling Light of Sunset (Jashi); and The Balcony Movie (Lozinski).

And as Dimitris Kerkinos, one curator at the festival told us at Modern Times: «what compensates for dramaturgy is the emphasis on detail. You see something that may seem boring at the beginning, but the more you watch, the more you discover details that make what you’re watching exciting.» Just like in Homo Sapiens, I could add.

As Kerkinos also underlined in a festival text, isn’t it that in observational cinema, the filmmaker becomes a kind of filter and less a director? Observation is based on a selection process since «we only see what we look at». And with the idea of a «cinema of duration» (going back to André Bazin), the emphasis is on events and continuity – where the details substitute dramatic tension, and authenticity replaces artificial excitement. With a revealing rather than explaining, the audience engages in active exploration. Just as Grimshaw earlier wrote, where the spectators «reach their own conclusions based on the evidence presented.»

To see again

In the documentary Shoah (1985) on Holocaust at the festival, we can see how Claude Lanzmann chose never to use archive photos but instead met several survivors, witnesses, and perpetrators – rather make us think and conclude (if that is possible) in this 9.5-hour doc… He is making the absence of the not seen event present. This by going to the places 40 years after Holocaust, looking with those who were there, at places of mass graves and crematoriums. Lanzmann also visited Chelmno, the little Polish city where the Nazis came with trucks full of contained Jews and killed them with the gas exhaust. What the other citizens from that time told him is revealing – such as their attitudes to the richer ‘Jews’ (they now lived in their houses) as just bystanders of such massacres. Somehow different to other witnesses who told him that at the train stations before transports to concentration camps – they tried to tell the Jews that they would get killed – as some arrived in cars (enthusiastic?) well dressed in their best clothes…

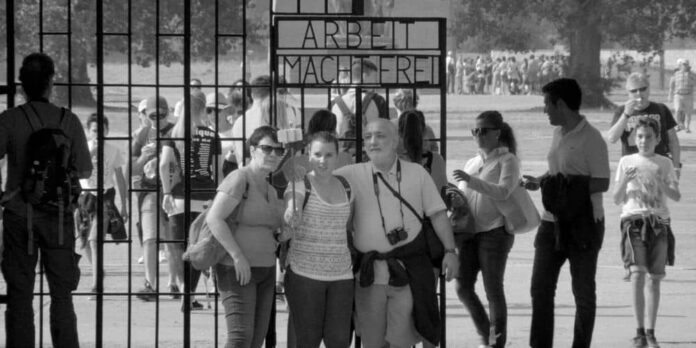

And what about Loznitsa’s Austerlitz (2016), as we in the festival could observe how he observed today’s observers of Sachsenhausen concentration or extermination camp. Fascinating nearly without voices, only long duration shots seeing tourists walking around (shot with a telephoto lens?), as they continuously took photos of themselves – as standing in front of the camp gate («Arbeit macht frei») or the gas ovens.

These two observational films give us, the audience, the freedom to make our own conclusions or free observations – on what ‘ordinary’ humans like those nazi killers, with sadism, precision, or humour – could do.

Did these films turn from reason to feelings – from information to life? From the individual one-character to the surrounding society and earth? At least such films are not ‘journalism’ and maybe teach us, if we are patient enough as Kerkinos was saying in Thessaloniki, to observe better and ‘see’ again with the wonder of early cinema – in our daily hectic modern times where consumerism dominates.